F# handling the option type

Intro

The steady march towards learning F# continues. This time lets look at the option type, what it is, how it compares to nullables in C# and the basics of how you are supposed to deal with it. I originally started this post because I was dealing with option in a lot of my exploratory code, and the things I’ve read online about options implied they were special in some ways, but the further through I got the more I realise they are really just the F# version of the Nullable type in C#, its how they are handled functionally thats special.

First the C# Nullable type

The closest relative to the option type in C# world is the Nullable<T> type. Which allows you to declare something thats not assignable to Null (e.g. an int) as nullable, and has properties that declare whether the variable is assigned a value or not, and gives you access to the value. For example:

int? test = null;

if (test.HasValue)

Console.WriteLine($"{test.Value}");*Prints nothing*

This piece of code will do absolutely nothing, because it declares the Nullable<int> “test” with the shorthand ? operator. It then proceeds not to assign anything to test, and to check its HasValue property to see if its Null. If it wasn’t Null it would then print its value to the screen. Now we could of course not do this null check like so:

int? test = null;

Console.WriteLine($"{test.Value}");System.InvalidOperationException: 'Nullable object must have a value.'

Of course, this code will throw an exception, which is one step further than the first code that did nothing. Finally, just for completeness:

int? test = 1;

Console.WriteLine($"{test.Value}");1

This prints the value 1, because thats whats been assigned to the nullable int. So how does this relate to F#?

On to F# options

Well, functional languages don’t tend to work with nulls, instead they deal with something called a maybe or in F# (and OCAML) world option. In F# you declare something as an option type by prefixing it with the words Some for a value or None for no value. For example:

let x = Some 41;

x |> string |> fun x -> printfn "%s" xSome(41)

What this piece of code is effectively saying is that x may contain an integer value of 41, BUT consumers of this variable need to make sure they handle the case where it doesn’t exist. Fortunately for our example case above, theres an automatic conversion to a string for the option type and we got “Some(41)” printed to the console.

Just to show the None case:

let x = None;

x |> string |> fun x -> printfn "%s" x*Prints nothing*

We’ve assigned None, and we got nothing printed, as you’d expect as long as the string conversions works correctly.

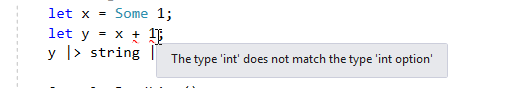

This is almost like for like how Nullable works in C#, except F# explicitly prints Some when converting to a string, and C# doesn’t. So.. if this is the same as a Nullable type in C# it follows that we can’t pass the variable directly to an int parameter:

And that turns out to be true, the compiler has rejected this code because the type option and int are incompatible for the + operator. So how should we handle an optional type then?

The old (bad) nullable style handling

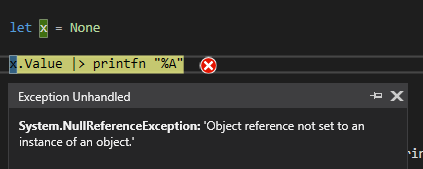

Of course, we could handle this case the same way as we do with Nullable in C#. Option provides the methods

IsSomeIsNoneValue

These work in much the same way as HasValue and Value, and calling the Value function without first checking if there is a value will result in an exception.

You could work away using these, writing if statements just like in imperative languages, but because this is the functional world, we don’t have to do that, instead we can use some of the built in language features to assist us to work in a way where exceptions can’t really happen, and None values are checked at compile time.

Pattern matching

One of the really powerful features in F# is pattern matching. Its pretty useful for handling option, its sort of a really concise switch statement. We can change our add function from above that failed to compile to correctly handle our option:

let x = Some 41;

let addOption x y : int = match x with

| None -> 0 + y

| Some x -> x + y

let y = addOption x 9;

y |> string |> fun x -> printfn "%s" x50

This time, we’ve handled that option type by creating a function called addOption, all that function does is decide how to handle the logic of adding the two numbers together, either with a default value for the None case, or with the actual value. The pattern matching syntax looks a little weird at first, but you get used to it, its basically match <variable> with | where | is the separator for each case. Within the first case we match x with None, this is our condition where x isn’t set, so we declare it as 0 + y, which has no effect. In our second case, we say Some x which checks that x has a value, and then we use x as a standard integer value in the corresponding function.

This is slightly different to how we’d have handled this in C#, you wouldn’t normally reach for the switch statement in this situation. However in functional land, functions, and the match statement are so easy to create, small and concise that this code makes a lot more sense. Its also quite reusable now, you can use this for adding any optional int, and avoid the possibility of exceptions due to improper handling of the option.

Of course we can also refactor this code into a higher order function, and make it much more reusable.

The higher order function version

Higher order functions are functions that take another function and operate over that function and associated data. For C# developers probably the easiest example is a Lambda Select statement, e.g.

var items = new[] {1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6};

items.Select(x => x.ToString());The select function, is equivalent to F# map, it takes the items and applies a function x => x.ToString() to each item. The important thing to understand here is that x => x.ToString() is just a function we define and are passing to the Select function, the Select function itself will just consist of the functionality to apply the passed function to the items array. So Select is a higher order function, it doesn’t do much by itself, but it facilitates doing many different things to our items collection just by taking that function as an argument.

Back to our F# then, lets assume we want to multiply our optional numbers as well. We know that for an addition our Identity (i.e. the empty case if you remember about monoids) 0, as any value + 0 will just return the original value. For multiplication, our Identity is 1 because 1 multiplied by any value just returns the original value too. So we need to pass in our identity, we also need to pass in the function for the operation (either + or -):

let x = Some 41;

//1

let optionOperation identity func x y = match x with

| None -> func identity y

| Some x -> func x y

//2

let add = optionOperation 0 (+)

let multiply = optionOperation 1 (*)

//3

add x 9

|> string |> printfn "%A"

multiply x 2

|> string |> printfn "%A""50"

"82"

- So in this code we’ve renamed

addOptiontooptionOperationand added two preceeding arguments,identityandfunc.identitytakes our default value for an operation for when our value is null.funcis our operation. We then use pretty much the same code asaddOption, but we replace the + with func before the two argumentsfunc x yand in ourNonecase we pass the identity. - These two lines are where the magic happens, we partially apply our

optionOperationfunction for add and multiply. Foraddwe pass 0 as our Identity and we wrap the plus infix operator in brackets(+)which turns it into a normal function that can be passed as an argument. We do exactly the same for the multiply, but with 1 and(*). - Finally in 3 we call our

addandmultiplyfunctions (which are now functions in their own right), and pipe them through to be printed.

Our add and multiply function are also monoids

This is quite a neat solution, and it means we can reuse our option logic for different types too if we want. The optionOperation can really run on any type now, with an identity and a function to apply. Lets append a function that concatenates two strings:

let concat = optionOperation String.Empty (fun x y -> x + y)

let z = Some "I have been "

concat z "concatenated" |> string |> printfn "%A""I have been concatenated"

Null should not be used, if its empty, its an option

An important major distinction between F# and C# is that nothing should really be assigned NULL . Instead option is used, for everything, if it might not exist it is an option, and the compiler mostly forces you to handle the empty case, although as discussed not if you revert to the functions on option itself. In contrast in C# only types that can’t inherently be null can be dealt with explicitly using the Nullable<T> type. Although C# 8 is about to add an option to change that.

For an example of F# allowing the use of option everywhere, heres a Tuple:

let x = Some (1,2,3, "Fred")

x |> string |> printf "%A""Some((1, 2, 3, Fred))"

And we get the printed “Some” value as expected. And if you wanted to use the value within the tuple, you can pattern match just like with standard types. e.g.

let x = Some (1,2,3, "Fred")

x |> string |> printfn "%A"

let isFred x = match x with

| None -> false

| Some (_,_,_,d : string) -> d = "Fred"

let y = isFred x |> string

y |> printfn "%A"

let z = isFred None |> string

z |> printfn "%A""Some((1, 2, 3, Fred))"

"True"

"False"

Note: Here we use _ in our pattern match for the tuple which denotes that we don’t care about that particular value.

Built in helper functions

option also has its own set of helper functions in the Option module. These assist in the processing of option types much like the standard list operations a couple of examples are:

Option.map

applies a function to the option where the value exists:

let x : int option = Some 1

let x1 : int option = None

x |> Option.map(fun x -> x.ToString()) |> printfn "%A"

x1 |> Option.map(fun x -> x.ToString()) |> printfn "%A"Some "1"

null

Interestingly this prints

let x : int option = Some 1

let x1 : int option = None

x |> Option.map(fun x -> x.ToString()) |> (fun x -> x.IsNone) |> printfn "%A"

x1 |> Option.map(fun x -> x) |> (fun x -> x.IsNone)|> printfn "%A"false

true

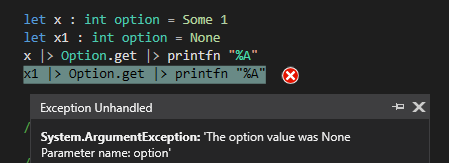

Option.get

returns the value stored in the option.

let x : int option = Some 1

let x1 : int option = None

x |> Option.get |> printfn "%A"

x1 |> Option.get |> printfn "%A"1

This prints 1 then throws an exception, presumably because its just calling x.Value inside that method, similarly to the map, this is not really ideal behaviour and I think I’d rather use a specific pattern match.

defaultArg

Another particular function of interest is defaultArg, which gets you the value or default for the option you pass.

defaultArg None 0 |> string |> printfn "%A"

defaultArg (Some 1) 0 |> string |> printfn "%A""0"

"1"

There are a whole bunch of other method types available, I won’t list them all, but if you use them, its probably worth working out their behaviour for the None case. Its more functional to avoid nulls and exceptions, and with the tools at your disposal to do this, theres not really a reason not to.

Summary

After all this, they’re a lot like nullables really aren’t they. F# Just provides much better tools to handle them, as long as you avoid the exception causing/null returning functions.